Tulane Database Brings Historic Activism to the Forefront

Elisabeth McMahon, associate professor of History and Africana Studies in the School of Liberal Arts, holds a folder of letters that are part of the African Letters Project, a free database that consists of over 5,600 letters written between Americans and Africans spanning from 1945 to 1994, during the decolonization era in many African countries. The database was created by McMahon, in collaboration with the Amistad Research Center and Tulane students. (Photo by Rusty Costanza)

August 23, 2022

Elisabeth McMahon, associate professor of History and Africana Studies in the School of Liberal Arts at Tulane and a Newcomb Fellow, in collaboration with the Amistad Research Center and Tulane students, created a database of letters written between Americans and Africans called the African Letters Project (ALP). The letters in the ALP highlight the connections between the two regions during the era of decolonization, while making that history accessible to all.

The African Letters Project is a free database that consists of over 5,600 letters written between 1945 to 1994, during the decolonization era in many African countries. McMahon’s initial idea for the database was to highlight more African American activists who supported independence movements throughout Africa during that period of history.

“Often when we think of the connections, during decolonization, it’s often white activists that are highlighted, the white American activist,” she said.

“A history that so often gets ignored (is) the role of African Americans in the United States pushing against apartheid and pushing for decolonization.”

Elisabeth McMahon, associate professor of History and Africana Studies

McMahon pulled part of her inspiration for the project from the documentary film “Have You Heard from Johannesburg?,” which chronicles African American anti-apartheid activism leading up to the signing of the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986.

“A history that so often gets ignored (is) the role of African Americans in the United States pushing against apartheid and pushing for decolonization,” she said. “I want to have that history more widely known.”

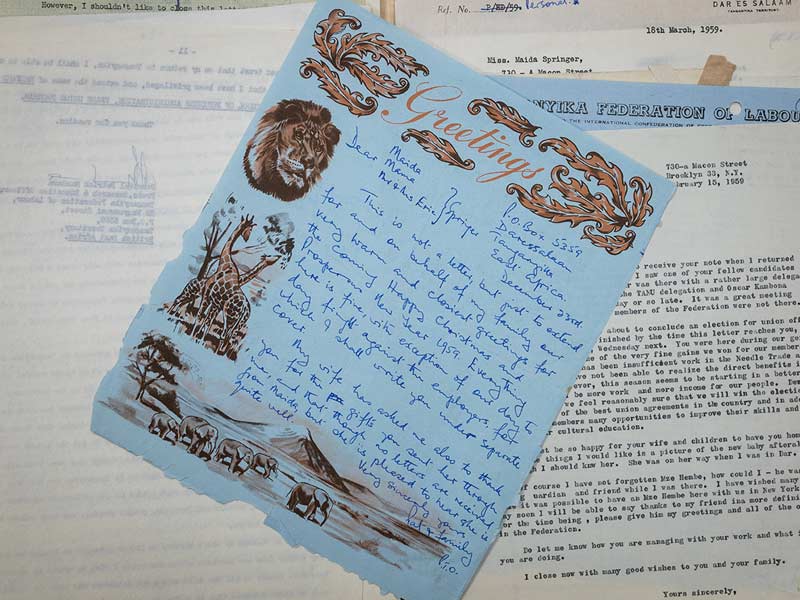

Through its partnership with the Amistad Research Center, the database includes collections of letters written by Maida Springer Kemp, the first African American labor union organizer hired by the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations to work in Africa. Throughout the 1950s, Kemp supported the emergence of African unions, often challenging colonial laws in those countries. Documents of the American Committee on Africa, which was dedicated to supporting the anti-colonial and anti-apartheid movements across Africa during the mid-to-late 20th century, are also included. The next collections that will be added come from two leading African Americans, including that of Dr. Marguerite Cartwright, an actress, journalist, sociologist and diplomat, and Dr. James H. Robinson, founder of Operation Crossroads Africa, a nonprofit volunteer organization that builds connections between Africans and Americans through cross-cultural experiences and service projects and was the prototype for the Peace Corps.

The collection also includes links to photos of scanned letters along with useful historical information such as the names and genders of the letter writers, dates, the topics of the letters, individuals and organizations mentioned, and the countries from which the letters were sent and received. Student researchers and those pursuing service learning through McMahon’s Africana Studies courses have contributed to the database by adding this essential information.

The website on which the database is housed was built by students in Newcomb Institute’s Digital Research Internship Program. This project was sponsored by Newcomb Institute’s Digital Research Internship program, where an interdisciplinary cohort of undergraduate interns developed the website and provided digital humanities support.

McMahon said students from all disciplines have contributed, offering non-history majors the opportunity to also learn historical research skills. Along with academic support, students gain emotional intelligence skills, too.

“When you start to read other people’s letters, which can be so personal in ways that they (students) get really excited about, it can help them build empathy as they go into their future careers,” McMahon said.

The database also serves as a form of restitution to African scholars, she said, making archival material related to African history globally available.

“Americans go to African countries; we work in the archives and we use those materials, and we make our careers. Yes, there are history books written now for various African locations and places, but it doesn’t quite help those scholars all the time.”

In addition to working with letters from other archives in the future, McMahon hopes to eventually add letters from local community members who might have “letters from an uncle or an aunt, or even their parents, who wrote letters with somebody in Africa.”

The website includes data visualization tools to help scholars, new and seasoned, in their research.

“(It’s) trying to give people some possibilities for open access materials,” she said. “A piece of this project has always been about using it as a teaching tool for digital humanities work for other scholars to be able to support their students.”

To access the African Letters Project, click here.

A letter written to Maida Springer Kemp, the first African American labor union organizer hired by the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations to work in Africa, is one of the many letters available through the database. (Photo by Rusty Costanza)