Are Climate Crises Increasing Domestic Violence in New Orleans?

By Anita Raj, PhD1, Taylor Robison 2, and Tarik Benmarhnia, PhD3

October 1, 2023

From April to June 2023, New Orleans saw a spate of femicides, i.e., the killing of a woman by an intimate partner (1,2). All nine women were Black, and all were killed by a gun (1,2).

There is no question that systemic racism and the preponderance of guns affect Black women’s risk for femicide in New Orleans and nationally. A higher risk for femicide in this context may also be linked to growing gender inequities in the state and related structural determinants, including those related to recent restrictions on abortion access. Prior research documents that states characterized by greater gender inequity (considering health, labor, and empowerment dimensions) have higher rates of femicide (3). Economic factors, too, may be at play. Prior evidence from the U.S. reveals that economic recession increases the risk for IPV (4). However, these issues alone cannot explain the rapid increase in femicide seen from April to June. Concerns related to systemic racism, gun access, restricted abortion access, and economic recession have been sustained concerns prior to and after the April to June period. We propose that climate-sensitive events, including extreme heat or extreme precipitation, could be associated with an increased risk of femicide in New Orleans during this period. If so, we may continue to see escalations in femicide in light of growing climate crises in our region.

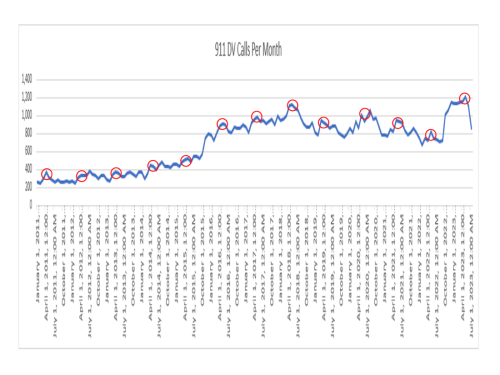

Figure 1. Orleans Parish Domestic Violence 911 Calls, January 1, 2011 to July 1, 2023

A look at the publicly available data on domestic violence 911 calls from the period of January 1, 2011, to July 1, 2023, shows a pattern of spikes in calls every April to August across all years (5). (See Figure 1.) April in New Orleans marks a period of increased precipitation until August and, relatedly, an increase in power outages. Precipitation levels in April and May are now higher than historical averages (6). June to August are typically the hottest months in the state, and this year, the state has seen the hottest temperatures on record for these months. This period also coincides with children being out of school for their annual holidays, potentially contributing to rising household costs. The etiological role of extreme heat on increasing aggressive behaviors has been widely described (7,8), which suggests that such concomitant increases may be related. A few possible mechanisms have been proposed by Parkinson (9) to explain how climate-sensitive events such as extreme heat or floods and gender-based violence (GBV) can be linked and include: i) increasing compounded vulnerabilities for women intensifying abusive and controlling behaviors; ii) the intersection with food and economic insecurity, job loss, poverty and the disappearance of relatives which can trigger mental stress; iii) physical displacement, loss of support and protection from the community. Certainly, the impact of Hurricane Katrina as well as more recent hurricanes, would support these claims and, further, demonstrate how these disproportionately burden Black women. Yet, there is a notable absence of epidemiological evidence in this area, which prevents the documentation of potential preventive strategies that can be experimented (10).

Cross-national research demonstrates that heat waves precede intimate partner violence (IPV) incidents, as indicated by both emergency calls and femicide (11). We lack studies from the U.S. documenting the effects of precipitation levels or power outages on IPV, but data from low- and middle-income country contexts indicate that heavy rains and flooding increase the risk for IPV directly and indirectly due to water insecurity (12). Research on power outages in North America also reveals increases in criminal behavior and financial distress following power outages (13), which can, in turn, increase the risk for IPV. These negative effects of climate events and power outages disproportionately burden Black and poor communities, contributing to IPV and health disparities.

These issues are not just important for IPV but also for maternal health. Louisiana is 5th in the nation in terms of femicide (14) and 4th in the nation in terms of maternal mortality (15), and femicide is the leading cause of death for pregnant and postpartum women (16). All but one of the women killed by their partner in New Orleans in the past few months were mothers (1). Given that climate concerns are also well-documented risk factors for maternal and neonatal health (17), it is paramount that we understand these issues in tandem and in contexts where climate concerns exist and are rapidly escalating. Inadequate data on IPV, particularly in terms of geocoded data that can be linked with climate indicators, impedes our ability to capture this information.

We need more research on climate events and IPV to help understand whether and how these affect IPV and femicide and racial/ethnic inequities in these concerns. We must prioritize research on these issues in the U.S. to have the necessary evidence to address climate-related risks and their social and health consequences effectively. The lack of prioritization of data and research on these issues and the inadequacies of our responses to climate crises are killing women and may be disproportionately killing Black women in the South.

As we start Domestic Violence Awareness Month in New Orleans, let’s do so with an awareness that this violence is not just disproportionately affecting those groups already disadvantaged by systemic racism and economic inequalities but also those disproportionately affected by climate crises. Addressing domestic violence means addressing concurrent climate and economic crises.

References

- Wilkinson M. 911 calls reporting domestic violence surged in New Orleans in May and June: 'The problem is out of control.' Nola.com and The Times-Picayune. July 28, 2023. Accessed Sept 3, 2023. https://www.nola.com/news/crime_police/911-calls-reporting-domestic-vio…

- Henry DE. 'We're truly not valued': In New Orleans, Black mothers are increasingly the victims of gun violence. The 19th. Aug 9, 2023. Accessed Sept 3, 2023. https://19thnews.org/2023/07/new-orleans-black-mothers-gun-violence-vic…

- Campbell JK, Rothman EF, Shareef F, Siegel MB. The relative risk of intimate partner and other homicide victimization by state-level gender inequity in the United States, 2000–2017. Violence and Gender. 2019;6:4,211-218.

- Schneider D, Harknett K, McLanahan K. Intimate partner violence in the great recession. Demography. 2016;53(2):471–505.

- Orleans Parish. Domestic Violence 911 Calls, January 1, 2011 to July 1, 2023. Orleans Parish Communication District calls for service. Accessed Aug 20, 2023. https://data.nola.gov/Public-Safety-and-Preparedness/Calls-for-Service-…

- National Weather Service. New Orleans International Airport (MSY) Monthly and Annual 30 Year Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Accessed Sept 3, 2023. https://www.weather.gov/lix/newnormals

- Anderson CA. (2001). Heat and violence. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2001;10(1):33-38.

- Hsiang SM, Burke M, Miguel E. Quantifying the influence of climate on human conflict. Science. 2013;341(6151):1235367.

- Parkinson D. Investigating the increase in domestic violence post disaster: an Australian case study. J Interpersonal Violence. 2017;4(11):2333–2362

- van Daalen KR, Kallesøe SS, Davey F, Dada S, Jung L, Singh L, Issa R, Emilian CA, Kuhn I, Keygnaert I, Nilsson M. Extreme events and gender-based violence: a mixed-methods systematic review. Lancet Planet Health. 2022;6(6):e504-e523.

- Sanz-Barbero B, Linares C, Vives-Cases C, González JL, López-Ossorio JJ, Díaz J. Heat wave and the risk of intimate partner violence. Sci Total Environ 2018;10(644):413-419.

- Ross A, Mack EA, Marcantonio R, Miller-Graff L, Pearson AL, Smith AC, Bunting E, Zimmer A. A mediation analysis of the linkages between climate variability, water insecurity, and interpersonal violence. Climate and Development. 2023. Epub ahead of print.

- Andresen AX, Kurtz LC, Hondula DM, Meerow S, Gall M. Understanding the social impacts of power outages in North America: a systematic review. Environmental Research Letters. 2023;18(5), p.053004.

- Violence Policy Center. Female homicide victimization by males. Sept 20, 2022. Accessed Sept 3, 2023. https://vpc.org/revealing-the-impacts-of-gun-violence/female-homicide-v…

- CDC. Maternal deaths and mortality rates by state, 2018-2021. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Accessed Sept 03, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/maternal-mortality/mmr-2018-2021-state-data.pdf

- Wallace ME, Crear-Perry J, Mehta PK, Theall KP. Homicide During Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period in Louisiana, 2016-2017. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(4):387–388.

- Lokmic-Tomkins, Z., Bhandari, D., Watterson, J., Pollock WE, Cochrane L, Robinson E, Su TT. Multilevel interventions as climate change adaptation response to protect maternal and child health: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. 2023;13(7), p.e073960.

1. Executive Director of the Newcomb Institute and Nancy Reeves Dreux Endowed Chair, Tulane University; Professor Tulane School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine (email: araj@tulane.edu)

2. Director of Public Affairs & Ally Engagement, Louisiana Coalition Against Domestic Violence (LCADV) (email: taylor.robison@lcadv.org)

3. Associate Professor, Scripps Institute of Oceanography, University of California San Diego (email: tbenmarhnia@ucsd.edu)

Acknowledgment: Data used in this analysis were from the Orleans Parish Communication District calls for service. Missy Wilkinson, MFA, a staff writer at the Times-Picayune, provided us with these data and also featured them in her July 2023 Times-Picayune article on the increase in domestic violence 911 calls from April to June 2023.

For more information on this work, please contact:

Anita Raj, PhD, MS she/her/hers

Executive Director, Newcomb Institute of Tulane University

Professor, Tulane School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine

The Commons, Suite 301, 43 Newcomb Place, New Orleans, LA 70118

newcomb.tulane.edu/

c/o Executive Administrative Assistant: Laura Kreller; lkreller@tulane.edu | 504-247-1639